In a world where millions suffer from hunger and vast amounts of food go to waste, food recovery emerges as a powerful solution. But oftentimes, potential stakeholders and community members don’t understand the impactful systemic change that food rescue provides in how we address food insecurity and food waste.

Watch our January 2024 webinar:

"What People Don’t Get About Food Recovery: Why It Matters & How to Change That"

Defining Food Recovery

When entering into conversations with elected officials, foundations, or even others in the charitable food space, it’s common that the term “food recovery” is misunderstood or has incorrect assumptions tied to it. It’s important that we create a baseline understanding of what food recovery is, why it matters, and how it’s different from other solutions in the food waste and hunger space.

What people often picture when they hear the term “food recovery” is more of a singular event, such as a church or pantry going to pick up surplus from their local grocery store because they have a distribution event coming up. In these instances, the focus is on collecting food to distribute to the community–it’s focused only on the nonprofit and the people they’re serving.

But at its core, food recovery extends beyond sporadic and intermittent rescues. It champions a systemic approach that tackles the intertwined issues of hunger and food waste simultaneously. Food recovery exists at the critical juncture of those two goals–reducing hunger and reducing food waste–both of which are equally important in the mission of food recovery. Unlike the conventional perception of local pantries picking up surplus food from grocery stores, it envisions a comprehensive strategy addressing both hunger and waste.

The Complex Landscape of Food Waste

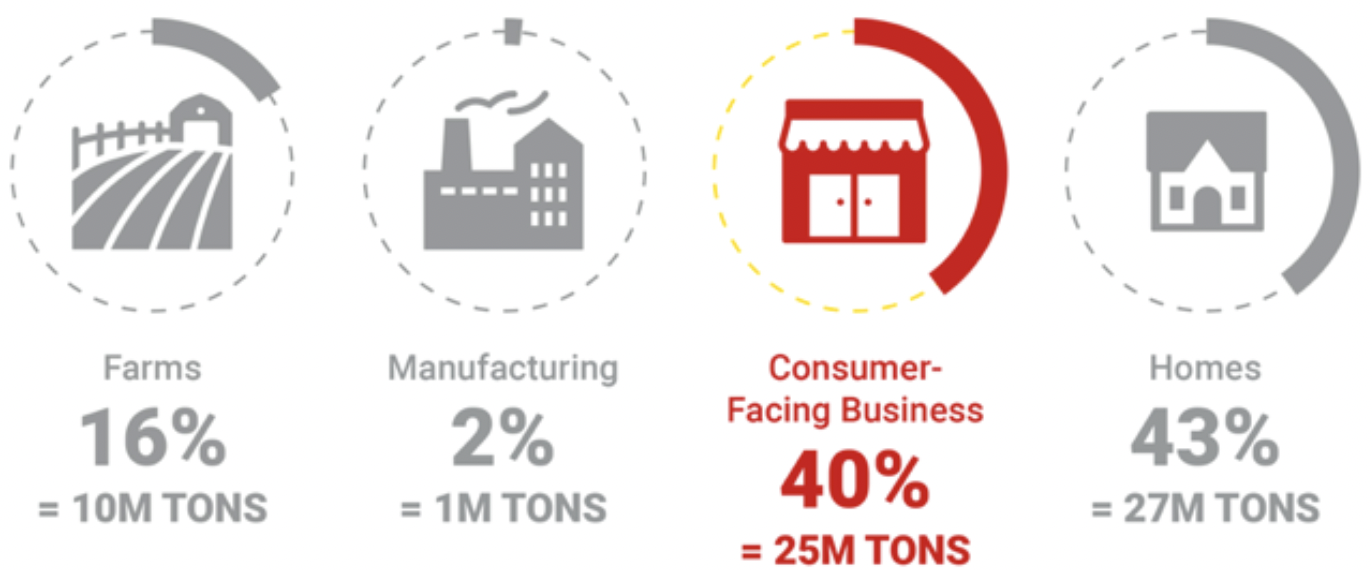

Food waste exists during every step of the food production and transportation process. Consumer-facing businesses, from supermarkets to cafes, contribute most significantly to the complex landscape of food waste before the food makes it into our homes.

In the United States, there are over:

- 26,149 conventional supermarkets

- 4,412 supercenters like Walmart or Target

- 150,174 convenience stores

- 3,507 natural/gourmet stores

These food retailers inhabit areas with varying population sizes, concentration of other food access points, and existence of charitable assistance sites.

The distributed nature of this waste demands a flexible donation transportation system to efficiently navigate this complex logistical tangle. And the challenge lies not only in the sheer number of food waste locations but also in the need for timely distribution. The traditional hub-and-spoke model of distribution doesn’t work for food recovery due to this expansive nature of surplus food; the time-sensitive nature of best by dates, ripening, and/or refrigeration; and diverse logistical accommodations needed by the food retailers and nonprofit distribution sites.

Food Recovery: Flexible Network Model

A flexible donation transportation system supported by a flexible and varied donation distribution network emerges as a solution, ensuring reliable pickups and efficient, on-time delivery to those in need. In this model, a fleet driver or volunteer picks up surplus food from the point of surplus and then directly delivers it to a community access point for potential immediate distribution. This model, as we’ll see, solves the bottlenecks on both the food donor and the distribution side of the system.

On the food retailer & donation side of operations, these partners have varying needs related to:

- Donation size

- Donation frequency

- One-time donation availability

- Highly distributed pick-up locations

The solution: Food rescue organizations can offer coordination of both one-time donations and regular weekly pickups of surplus food by utilizing a variable collection model employing volunteers PLUS either having or supporting fleet-based organizations. Depending on the size of the donation, having the infrastructure of both a truck fleet and volunteer network with personal vehicles ensures that any size donation can be picked up, even between highly distributed retailer locations. In this way, food recovery is focusing on the needs of the donor as well as the climate impact of food not being picked up. The goal is to maximize the food kept out of landfills, and that scale can be most efficiently achieved through a flexible logistics model.

On the nonprofit organizations distribution side, partners also have varying needs related to:

- Donation size

- Donation frequency

- Open hours

- Storage capacity

- Community needs

While it’s easy to slip into solely focusing on the nonprofit and the people they’re serving–just like the common misconception of food recovery–we must still consider the tandem goal of reducing food waste. Taking into account the needs of the nonprofit partner ensures this surplus food that many hands worked so hard to rescue doesn’t go to waste at the distribution site itself.

The solution: A flexible distribution network. Just as the coordination of picking up surplus food must be varied to accommodate diverse needs, such is required in food distribution, too! In order to scale and maximize the amount of food kept out of landfills, a food recovery organization must have a diverse distribution network to get the food to people who will eat it before it is no longer good. Many food recovery organizations have therefore turned to nontraditional nonprofits as food distribution partners such as subsidized housing, Head Start programs, WIC offices, or job training centers.

The expansion of the distribution network means good food can get to people who need it, almost directly, seven days a week and regardless of quantity–whether the rescue is one tray of deli sandwiches or 10 pallets of cucumbers. Not only is this critical in ensuring a grocer’s surplus does not become a nonprofit’s garbage, but it also means greater opportunities for food access in the community. Initiatives like providing subsidized housing residents with groceries exemplify the transformative power of community-focused approaches. Community collaboration and cooperation become vital in meeting the dual goals of reducing food waste and ensuring equitable access to nourishment.

How to frame the conversation with local government, funders & community members:

Don’t assume they know what food rescue is. And don’t let them assume they know either! Paint the picture of what food recovery actually is, how it addresses a multitude of pain points, and how their support can result in a better community as a whole.

Identify what the new benefits will be:

- Reduction of waste

- Increased food access

- Nutrition security

- Climate impact

Identify key areas of difference with existing efforts. You are not just another food pantry or food bank! Food rescue operates much differently than many existing organizations, which means you can fill in the gaps that others are missing.

Be the AND not the OR. Food recovery does not replace food pantry or food bank operations. Food rescue isn’t about swooping in to compete with the same foods that are already successfully being rescued by other nonprofits. Being the “and” means approaching food retailers and seeing what gaps still exist, what foods aren’t being taken by these other organizations? We are filling in the gaps, and bringing some equilibrium to the food distribution system, with a focus on eliminating food waste at these consumer facing businesses as well as other charitable food locations.

Show them this is system-changing and therefore outcome-changing. Use your data as proof of impact on the community. While the cause of hunger and food insecurity is not something addressed by food recovery, people still need to eat while the entire system is being worked on and improved. And what improved food access provides goes beyond the mitigation of one major human need – it removes a major worry, leads to improved health and focus, and ultimately opens the door to more opportunities for community members experiencing food insecurity.

Government Intervention & Legislative Impact

Government involvement, exemplified by California’s SB1383, marks a significant step towards legislative solutions for food waste and food insecurity. In this bill, food retailers are required to donate a percentage of their edible surplus to food recovery organizations, to not only reduce food waste in the landfill but also address hunger in the community.

The Food Donation Improvement Act passed in Congress in December 2022. The legislation builds upon the 1996 Bill Emerson Good Samaritan Food Donation Act by clarifying and broadening liability protections for retailers to donate surplus food.

Driven by the broader context of climate change, interventions like these showcase the potential impact of policy in shaping a sustainable future.

A Call to Action

In a world grappling with food insecurity and environmental challenges, food recovery emerges as a responsibility, not just a choice. It’s about revolutionizing the narrative, dispelling myths, and actively participating in a collective effort to make a lasting impact. The time for change is now, and the path forward involves embracing the transformative potential of food recovery.